Back in 2001, when we first began studying how regenerative cells (stem cells or more mature progenitor cells) enhance blood vessel growth, our group as well as many of our colleagues focused on one specific type of blood vessel: arteries. Arteries are responsible for supplying oxygen to all organs and tissues of the body and arteries are more likely to develop gradual plaque build-up (atherosclerosis) than veins or networks of smaller blood vessels (capillaries). Once the amount of plaque in an artery reaches a critical threshold, the oxygenation of the supplied tissues and organs becomes compromised. In addition to this build-up of plaque and gradual decline of organ function, arterial plaques can rupture and cause severe sudden damage such as a heart attack. The conventional approach to treating arterial blockages in the heart was to either perform an open-heart bypass surgery in which blocked arteries were manually bypassed or to place a tube-like “stent” in the blocked artery to restore the oxygen supply. The hope was that injections of regenerative cells would ultimately replace the invasive procedures because the stem cells would convert into blood vessel cells, form healthy new arteries and naturally bypass the blockages in the existing arteries.

As is often the case in biomedical research, this initial approach turned out to be fraught with difficulties. The early animal studies were quite promising and the injected cells appeared to stimulate the growth of blood vessels, but the first clinical trials were less successful. It was very difficult to retain the injected cells in the desired arteries or tissues, and even harder to track the fate of the cells. Which stem cells should be injected? Where should they be injected? How many? Can one obtain enough stem cells from an individual patient so that one could use his or her own cells for the cell therapy? How does one guide the injected cells to the correct location, and then guide the cells to form functional blood vessel structures? Would the stem cells of a patient with chronic diseases such as diabetes or high blood pressure be suitable for therapies, or would such a patient have to rely on stem cells from healthier individuals and thus risk the complication of immune rejection?

The complexity of blood-vessel generation became increasingly apparent, both when studying the biology of stem cells as well as when designing and conducting clinical trials. A large clinical study published in 2013 studied the impact of bone marrow cell injections in heart attack patients and concluded that these injections did not result in any sustained benefit for heart function. Other studies using injections of patients’ own stem cells into their hearts had led to mild improvements in heart function, but none of these clinical studies came close to fulfilling the expectations of cardiovascular patients, physicians and researchers. The upside to these failed expectations was that it forced the researchers in the field of cardiovascular regeneration to rethink their goals and approaches.

One major shift in my own field of interest – the generation of new blood vessels – was to reevaluate the validity of relying on injections of cells. How likely was it that millions of injected cells could organize themselves into functional blood vessels? Injections of cells were convenient for patients because they would not require the surgical implantation of blood vessels, but was this attempt to achieve a convenient therapy undermining its success? An increasing number of laboratories began studying the engineering of blood vessels in the lab by investigating the molecular cues which regulate the assembly of blood vessel networks, identifying molecular scaffolds which would retain stem cells and blood vessel cells and combining various regenerative cell types to build functional blood vessels. This second wave of regenerative vascular medicine is engineering blood vessels which will have to be surgically implanted into patients. This means that it will be much harder to get approval to conduct such invasive implantations in patients than the straightforward injections which were conducted in the first wave of studies, but most of us who have now moved towards a blood vessel engineering approach feel that there is a greater likelihood of long-term success even if it may take a decade or longer till we obtain our first definitive clinical results.

The second conceptual shift which has occurred in this field is the realization that blood vessel engineering is not only important for treating patients with blockages in their arteries. In fact, blood vessel engineering is critical for all forms of tissue and organ engineering. In the US, more than 120,000 people are awaiting an organ transplant but only a quarter of them will receive an organ in any given year. The number of people in need of a transplant will continue to grow but the supply of organs is limited and many patients will unfortunately die while waiting for an organ which they desperately need. The advances in stem cell biology have made it possible to envision creating organs or organoids (functional smaller parts of an organ) which could help alleviate the need for organs. One thing that most organs and tissues need is a network of tiny blood vessels that permeate the whole tissue: small capillary networks. For example, a liver built out of liver cells could never function without a network of tiny blood vessels which supply the liver cells with metabolites and oxygen. From an organ engineering point of view, microvessel engineering is just as important as the building of functional arteries.

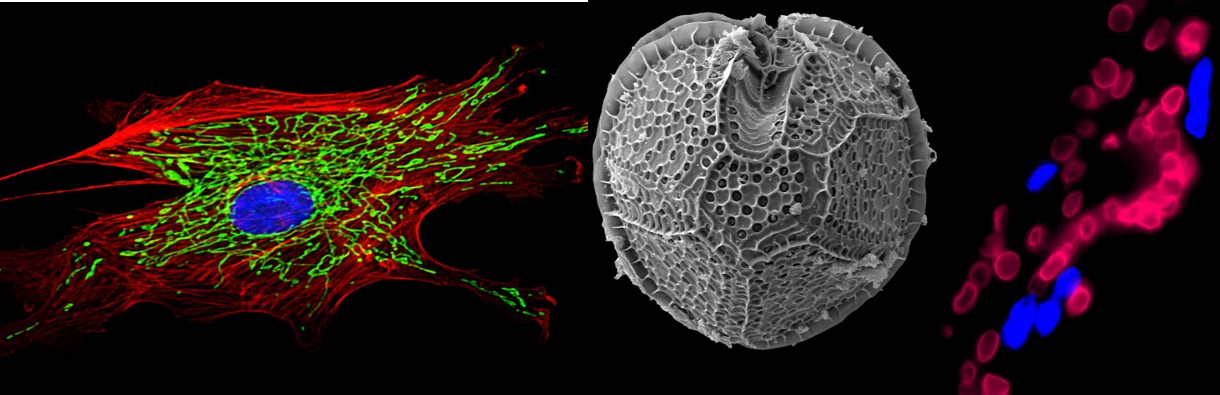

In one of our recent projects, we engineered functional human blood vessels by combining bone marrow derived stem cells with endothelial cells (the cells which coat the inside of all blood vessels). It turns out that stem cells do not become endothelial cells but instead release a molecular signal – the protein SLIT3- which instructs the endothelial cells to assemble into networks. Using a high resolution microscope, we watched this process in real-time over a course of 72 hours in the laboratory and could observe how the endothelial cells began lining up into tube-like structures in the presence of the bone marrow stem cells. The human endothelial cells were like building blocks, the human bone marrow stem cells were the builders “overseeing” the construction. When we implanted the assembled blood vessel structures into mice, we could see that they were fully functional, allowing mouse blood to travel through them without leaking or causing any other major problems (see image, taken from reference 3).

I am sure that SLIT3 is just one of many molecular cues released by the stem cells to assemble functional networks and there are many additional mechanisms which still need to be discovered. We still need to learn much more about which “builders” and which “building blocks” are best suited for each type of blood vessel that we want to construct. The fact that human fat tissue can serve as an important resource for obtaining adult stem cells(“builders”) is quite encouraging, but we still know very little about the overall longevity of the engineered vessels, the best way to implant them into patients, and the key molecular and biomechanical mechanisms which will be required to engineer organs with functional blood vessels. It will be quite some time until the first fully engineered organs will be implanted in humans, but the dizzying rate of progress suggests that we can be quite optimistic.

(An earlier version of this article was first published on 3Quarksdaily.com).

References and links (all of them are open access, so you can read them for free, including the original paper we published):

1. A recent longform overview article I wrote for “The Scientist” in which I describe the importance of blood vessel engineering for organ engineering:

J Rehman “Building Flesh and Blood“, The Scientist (2014), 28(5):48-53

2. An unusual and abundant source of adult stem cells which promote the formation of blood vessels: Fat tissue obtained from individuals who undergo a liposuction!

J Rehman “The Power of Fat” Aeon Magazine (2014)

3. The study which describes how adult stem cells release a protein (SLIT3) which organizes blood vessel cells into functional networks (open access – can be read free of charge):

J.D. Paul et al., “SLIT3-ROBO4 activation promotes vascular network formation in human engineered tissue and angiogenesis in vivo” J Mol Cell Cardiol (2013), 64:124-31.

Paul JD, Coulombe KL, Toth PT, Zhang Y, Marsboom G, Bindokas VP, Smith DW, Murry CE, & Rehman J (2013). SLIT3-ROBO4 activation promotes vascular network formation in human engineered tissue and angiogenesis in vivo. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology, 64, 124-31 PMID: 24090675